Eight hundred life spans can bridge more than 50,000 years. But of these 800 people, 650 spent their lives in caves or worse; only the last 70 had any truly effective means of communicating with one another, only the last 6 ever saw a printed word or had any real means of measuring heat or cold, only the last 4 could measure time with any precision; only the last 2 used an electric motor; and the vast majority of the items that make up our material world were developed with the life span of the eight-hundreth person.

R.L. Lesher and G.J. Howick, Assessing Technology Transfer (NASA Report SP-5067) (1966)

Sunday, December 23, 2007

Quotation for the Day

Saturday, December 15, 2007

Eureka in the Hot Tub

This sounds almost impossible to believe but I had an Archimedes-like "Eureka Moment" the other night. And it even had to do with the displacement of water in a bath. Let me explain. I have been struggling for months to figure out why the venturi jets in our Florida home's hot tub work intermittently. Oh, the jets draw water all right but they don't pull in the air stream that makes for those refreshing bubbles. I have been asking everybody who seems to know anything about it why it doesn't seem to work. Or to be more exact, works only at times.

One way we've gotten the jets to bubble is to pull out the filter cartridge which is in line with the pump feeding the hot tub. When the filter is out, the pressure drop in the line goes down and the velocity of the water moving through the pipe goes up. Somewhere in the deep recesses of my mind, I remember Bernoulli's Equation which states that the pressure varies inversely with the square of the fluid velocity. Speed up the fluid and the pressure drops enough to suck air into the jets. The trouble with this is rather obvious. Who wants to go out and pull out the filter every time you want to use the hot tub?

A really smart pool guy came by the other day and looked over the situation. He looked at the location of the venturi air tube that comes out of the tub and diagnosed it as having been installed too low, hence the amount of water that had to be pulled through the tube to bring in air was too high. But the tube is set in concrete, not easy to move.

So back to my Eureka Moment. My son and I got in the tub the other night to try to puzzle out the problem. I displaced my volume of water out the overflow trough into the pool. The water surface level didn't change. But when I got out to get a towel I took my volume out of the pool, the water level dropped, and, "Eureka!", the bubbles started. The lower water level was just enough to pull the air into the venturi air tube. We were ecstatic to see that the tub worked and, wonder of wonders, Bernoulli's Equation told us why. The pressure is not only inversely related to the velocity of the fluid, it is also inversely related to the height of the column of water in the air tube. Lower the hot tub surface and the height goes down increasing the vacuum pressure to suck open the air tube. We finally understood how the system worked and with that knowledge we can make it work consistently.

So what did I learn out of all this? Observe carefully and make notes on what you observe. Look for correlations between changing one variable and the response in another parameter. Try to understand the physics. Hypothesize about what is happening but always be open to the happy accident, the Eureka.

Archimedes would surely have been proud of us. And Bernoulli, too. Centuries have passed since these two intellectual giants showed the way. There is something very comforting in seeing that the laws of physics are as applicable today as they were then.

I gotta run. The hot tub is calling.

Eiffel's Towers

When you stand under the web of steel that arches high over your head, you have to tilt back so far that you almost lose your balance. The scale is nothing if not monumental. It stands 1,047 feet tall. It took 50 engineers and designers 5300 blueprints to specify the structure known as the Eiffel Tower.

Today is the birthday of Gustave Eiffel who was born December 15, 1832 in Dijon, France. Who isn't familiar with the iconic Eiffel Tower? It has over-shadowed Paris since it was built in 1889. I can remember the first time I visited the tower. It was amazing! It never looked that large in pictures. I felt somehow humbled by its presence.

Gustave Eiffel didn't set out to become a structural engineer. While he did attend a technical college in Paris (École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures), he graduated not as an engineer but with a degree in chemistry. Life often rudely derails the best plans and young Gustave could not find a job as a chemist and took an entry level job managing part of a railroad bridge building project. He was good enough at his work that his supervisor gave him more and more responsibility building other bridges. Eiffel eventually set up a project management consulting company for structural engineering projects. The Eiffel Tower was an example of his work as contractor working in collaboration with Maurice Koechlin and Emile Nouguier, structural engineers, and Stephen Sauvestre, architect. The tower has long-since surpassed its original intended life of 20 years. The Tower now hosts over six and a half million visitors a year.

But this was not the first tower with which Eiffel was involved. When Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi sculpted the Statue of Liberty as a gift from France to the United States for the U.S. Centennial celebration, a scaffold of steel was needed to support the plates of Lady Liberty. Eiffel was contracted to design and build the pylon. The unique structure allows the 200,000 pounds of copper plates to move independently in order to reduce stresses on the overall Statue. So Eiffel has both his famous Tower in Paris and a less visible but equally technically impressive structure standing in New York Harbor.

Ironically, I have been to Paris to stand beneath (and ascend) the Eiffel Tower but I have never been to the Statue of Liberty in my own country. But regardless of my failing to make the journey, my hat is off to Gustave Eiffel. Few get a chance to create something that persists in the collective consciousness so strongly as the gracefully rising web of steel of his grand Parisian Tower. And while you can't see it as easily, his work supports that equally iconic statue that personifies America.

[Images from Wikipedia]

Thursday, December 13, 2007

Ready Kilowatt

I don't know why this image from my youth just popped into my head but I just remembered a character called Ready Kilowatt which was used by power companies to promote the use of electricity in the home. Ready had a stick-figure body made of lightning bolts and a light bulb for a head. I can clearly see him in my mind's eye gracing the Edison Sault Electric Company office in the town where I grew up. Ready was always so...peppy. He just exuded energy (but what else would you expect from a lightning bolt?).

According to Wikipedia, the Ready character was created in 1926 by the Alabama Power Company and then licensed to over 300 other power companies for use in promoting electricity usage in the home. Ready was bought by Northern States Power Company in 1998 but the promotion of electricity usage has fallen out of favor. With today's emphasis on conservation, having Ready telling us to use more of the juice seems rather old fashioned. I guess that NSP (now Xcel Energy) created an analog of Ready to promote gas usage but I don't remember seeing it (and we were NSP customers for years).

The icons of our culture change with the technology and the times. Ready Kilowatt would probably be indicted today in the court of world opinion for adding to the greenhouse gases driving climate change. Now we see reminders to save rather than consume. While I agree with the more environmentally sensitive era we are now in, I still kinda miss old Ready. But I also miss Howdy Doody and Sky King.

[Image of Ready Kilowatt from Wikipedia]

Tuesday, December 11, 2007

Vive la Difference!

I recently watched an interesting documentary titled, The Cutting Edge, Magic of Movie Editing. I was unaware of this, but it turns out that before movies had sound, film editing was largely a women's profession. The skills needed to cut and assemble film segments were seen to be something akin to sewing or needlework. It was also (like most 'women's work') anonymous. When sound tracks came to the movies, film editing began to be taken over by men because the sound track was somehow perceived to be more "technical". A more masculine approach to handle all this "technology" was needed.

Isn't it interesting that some aspects of technology are somehow seen to be the realm of men? I could understand this, perhaps, when the technology in question was blacksmithing or steel making, or laying railroad tracks. But even in those areas, more current times have shown that women are perfectly capable of what were once thought to be "high strength" professions.

I wonder if it isn't an even more fundamental issue that has to do with being in control of whatever is the driving force in our world. In prehistory, this would have been hunting food or making fire. In modern times, it is the technology that defines the world we live in. Gender roles die hard. Men just can't seem to give up the driver's seat in the car or the keys to the tool shed.

To be fair, many women have their own opinions on whether they like or dislike dealing with technology. One example I have heard from others and I can speak to personally is the Home Entertainment System. My son and I think that flipping a few settings on the remote control to get the TV, amplifier, cable box, and DVD in sync is no big deal (even though half the time we do have to push a few random buttons to get it to work). My wife and daughter represent most women, I think, when my wife says, "Give me a TV with one button for on and off and none of this ridiculous patching that has to be done to make it work!" Now, I understand what she is saying but honestly, isn't it more fun to have a cockpit of hardware to drive than simply to hit the power button?

Even big companies are waking up to the gender differences. Sony has studied the differences between what men and women want in home entertainment and is proposing different designs for each. Best Buy is even trying out a different retail space that is less "techie" in order to appeal to more women. Stay tuned for more products and stores that respect the differences.

It is hard to see where all this might lead. The cellular/wireless/FaceBook world we live in, particularly in the case of younger people, seems to be received equally well by both sexes. I don't think there is much difference between how young men and women text message or link up...but I admit I may just be out of touch.

What I know for sure is that I will never have to battle my wife for the control of the lawn mower or snowblower. Some things are best left to a man.

[Image from Wikipedia of an early film editing machine]

Sunday, December 9, 2007

Quotation for the Day

Some problems are just too complicated for rational logical solutions. They admit of insights, not answers.

- Jerome Wiesner

Thursday, December 6, 2007

To Err is Human

I have written previously about the professional way in which people employ the technologies in our daily lives (see Chatter in the Sky). Most of the time, we can depend on people to make the right decisions. Unfortunately, there are times when just the opposite happens.

This week is the anniversary of the Bhopal Disaster in India. Thousands of people were killed when methyl isocynate gas escaped from a holding tank at the Union Carbide facility during the early morning hours of December 3, 1984. The investigations and legal proceedings stemming from this disaster went on for years and led to the eventual sale of Union Carbide to Dow Chemical Company.

What caught my eye in reading about the disaster was the role of the people at the Bhopal plant. There was an audible external alarm that sounded when the gas leaked but the plant management quickly silenced the alarm so as not to panic the residents of the town. Many people continued to sleep while the toxic gas drifted over their homes. Even after the pulmonary symptoms developed, doctors were not informed of the nature of the leak so as to provide the correct care. Many people died unnecessarily.

It seems that the response in Bhopal is one that has happened enough times in other settings to be troubling. Examples abound of people who know the facts but withhold them for all the wrong reasons. Here are a couple more stories I have come across recently. In December of 1943, a German bomber sank an allied ship in the harbor at Bari, Italy. The ship, the SS John Harvey, contained a secret cargo of mustard gas that was being brought to Italy in case the Germans used this same poison on allied troops. Authorities on shore had no knowledge of the highly-classified cargo and as a result doctors did not know what was causing the resident's deadly symptoms. And they were not told. It is reported that the presence of the mustard gas was hushed up until after the war on the direct orders of Winston Churchill.

Here is another story. In September 1918, as many as 100 young soldiers were dying each day in Boston from the Spanish Flu. Despite the obvious pandemic, city officials refused to cancel the "Win the War for Freedom" parade through Boston thus exposing tens of thousands of people to the virus being shed by the young soldiers in the parade. The pandemic continued its rampage through the population.

Another more recent example is what took place in the Superdome in New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Tens of thousands of people were left abandoned for days in the richest country on earth.

Sometimes, intelligent people who can see a disaster unfolding fail us, why? Confusion during a crisis is one possible explanation. Pure incompetence is always has to be considered but I believe that most people who are in decision-making positions are not stupid. I suspect that it has more to do with denial and fear of the bad news coming back to roost with these decision makers, even more so when they know that they have been systematically compromising the very technologies they are there to manage. It is an all too human response. .

I doubt we can ever expect a change in human nature. But we can do more to provide fail-safe technology and adequate warnings when disasters do occur. The company I worked for had to provide a complete inventory of chemicals to both the federal and local authorities in the event of a fire or problem in one of our labs. But these inventories came as a result of fires in other labs in other companies. It is like airline safety - it is built on the graves of the dead. We may complain about the high cost of regulations and the costs of technology backup systems. But history teaches us that people are not always dependable in a pinch.

To err is human....

This week is the anniversary of the Bhopal Disaster in India. Thousands of people were killed when methyl isocynate gas escaped from a holding tank at the Union Carbide facility during the early morning hours of December 3, 1984. The investigations and legal proceedings stemming from this disaster went on for years and led to the eventual sale of Union Carbide to Dow Chemical Company.

What caught my eye in reading about the disaster was the role of the people at the Bhopal plant. There was an audible external alarm that sounded when the gas leaked but the plant management quickly silenced the alarm so as not to panic the residents of the town. Many people continued to sleep while the toxic gas drifted over their homes. Even after the pulmonary symptoms developed, doctors were not informed of the nature of the leak so as to provide the correct care. Many people died unnecessarily.

It seems that the response in Bhopal is one that has happened enough times in other settings to be troubling. Examples abound of people who know the facts but withhold them for all the wrong reasons. Here are a couple more stories I have come across recently. In December of 1943, a German bomber sank an allied ship in the harbor at Bari, Italy. The ship, the SS John Harvey, contained a secret cargo of mustard gas that was being brought to Italy in case the Germans used this same poison on allied troops. Authorities on shore had no knowledge of the highly-classified cargo and as a result doctors did not know what was causing the resident's deadly symptoms. And they were not told. It is reported that the presence of the mustard gas was hushed up until after the war on the direct orders of Winston Churchill.

Here is another story. In September 1918, as many as 100 young soldiers were dying each day in Boston from the Spanish Flu. Despite the obvious pandemic, city officials refused to cancel the "Win the War for Freedom" parade through Boston thus exposing tens of thousands of people to the virus being shed by the young soldiers in the parade. The pandemic continued its rampage through the population.

Another more recent example is what took place in the Superdome in New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Tens of thousands of people were left abandoned for days in the richest country on earth.

Sometimes, intelligent people who can see a disaster unfolding fail us, why? Confusion during a crisis is one possible explanation. Pure incompetence is always has to be considered but I believe that most people who are in decision-making positions are not stupid. I suspect that it has more to do with denial and fear of the bad news coming back to roost with these decision makers, even more so when they know that they have been systematically compromising the very technologies they are there to manage. It is an all too human response. .

I doubt we can ever expect a change in human nature. But we can do more to provide fail-safe technology and adequate warnings when disasters do occur. The company I worked for had to provide a complete inventory of chemicals to both the federal and local authorities in the event of a fire or problem in one of our labs. But these inventories came as a result of fires in other labs in other companies. It is like airline safety - it is built on the graves of the dead. We may complain about the high cost of regulations and the costs of technology backup systems. But history teaches us that people are not always dependable in a pinch.

To err is human....

Quotation for the Day

Every production of genius must be the production of enthusiasm.

Benjamin Disraeli

(1804-1881, British statesman, Prime Minister)

Wednesday, December 5, 2007

The Tin Goose

I was talking to a man today who commented that he was almost born on a Ford Trimotor airplane on a flight from Rattlesnake Island in Lake Erie. Rattlesnake Island is a private island which is the home of the exclusive Rattlesnake Island Club. The man volunteered that he was 48 years old. I looked up Rattlesnake Island and apparently it is still being served by this same airplane today. I don't know why I was so surprised. Maybe the Ford Trimotor seems like something you would see in the Smithsonian (which you can) or in an old Humphrey Bogart movie. But for the plane to still be flying a regular run is remarkable.

[Image from Wikipedia]

The Ford Trimotor (affectionately nicknamed the Tin Goose) came out of an early interest by Henry and Edsel Ford in the newly emerging field of aviation. An engineer named William Stout trying to start an airplane company sent letters to leading industrialists asking for $1000. The letter stated, "For your one thousand dollars you will get one definite promise: You will never get your money back." Henry and Edsel and 18 other investors put up the money to get Stout started.

By 1925, Henry Ford wanted control of the company and bought it from Stout. The company continued to operate until June of 1933 when Ford's interest in aviation waned in the face of the much more successful aircraft being designed by Douglas Aircraft Company. But in the eight years it was in operation, the Ford aircraft operation produced about 200 Trimotors. Many of these aircraft had long and productive careers.

The one in the Smithsonian, for example, started with American Airlines and was then sold many times over the years for use in hauling cargo and even crop dusting. It ended up being converted into a dilapidated 'house' outside of Mexico City, complete with a stove pipe through the roof of the fuselage. American Airlines repurchased the plane and restored it to its original condition, using it for public relations flights. It even made the first commercial flight out of the newly-opened Dulles Airport outside Washington, D.C. in November, 1962. American Airlines donated the plane to the Smithsonian when it was no longer used for public relations and it now hangs in the Air Transportation gallery.

I don't often hear someone casually mention that they had flown multiple times on a Ford Trimotor. It's like hearing someone say they drive a Stanley Steamer. The point here is that technologies don't disappear overnight. As long as they perform a useful function in a serviceable and cost-effective manner, even old technologies can still be found side-by-side with the latest New-New Thing. The Ford Trimotor flies at a cruising speed of 90 knots and lands on a dime, perfect for Rattlesnake Island. You have to admire the Tin Goose for doing the job so well for so long. Here's to another 75 years of service!

Tuesday, December 4, 2007

Something's Happening Here

I was reading an interesting article written by Kate Greene that appears in the November/December issue of MIT's Technology Review magazine. The article, titled "What Is He Doing?" is about Evan Williams, the founder of Blogger (host of this blog) and now the founder of a new company called Twitter. On first reading this article, I thought Twitter sounded fairly pointless. The concept of this dot-com company is to have people answer a simple question in 140 characters or less: "What are you doing right now?" The Twitter member files an answer via their computer or cellphone. The messages (known as tweets) can say something as simple as "Sitting at my computer typing my daily blog." These little missives are then automatically sent to a pre-determined list of friends. Tweets can be entered as many times a day as you like. Some people update their tweets a dozen times a day. There are estimated to be a half a million people engaged in this zany activity.

Despite the numbers, I wonder who wants to read all this dribble? Do I really want to know what my friends are doing at any given moment of the day? Do I want to tell them what I am doing? Given that I am somewhat beyond the Millennial Generation, my first response is that this is BORING! But my second thought is... I'm not so sure.

People have an amazing capacity to socialize and connect. What would tell me more about a friend, an occasional e-mail or a tweet that describes the minutiae of my friend's day? Maybe the latter. But this troubles me in other ways as well. Is this a voluntary form of invasion of privacy (if we do it voluntarily)? Why spy on someone when they will Tell All anyway?

People have long speculated on the emergence of a "global consciousness". Various names have been applied to this idea: Giai, Metaman, the Global Brain, or the Nooshere. A common thread runs through this sort of thinking: there is a consciousness on the planet that is the integration of all of our individual consciousnesses. We seem to be steadily progressing toward a world where we are so intimately connected that maybe we really will have a Global Oneness. Maybe Twitter (and the host of recent clones that have appeared to exploit the same concept) is the next step after e-mail and cellphones to link up our digital lives.

What is a little creepy to me about all this is that if there really is such a thing as a global brain, will there be a time when I am not really acting on my own free will (even if I think I am) but rather fulfilling some small part of the larger brain think?

I am not rushing out at the moment to start sending tweets to my friends. I have always been someone who sorta hangs at the edge of the "technology dance floor" to see who is joining the party. I was late to the cellphone phenom and only recently started this blog so who knows? Before you know it, I may be spilling my boring guts to one and all. Too bad for all my friends. But that's the price for a really smart planet.

Monday, December 3, 2007

Father of the National Weather Service

Today is the birthday of Cleveland Abbe who was born on this date (December 3) in 1838. Abbe is widely considered to be the father of the U.S. National Weather Service. The Weather Service was originally created as a branch of the U.S. Army Signal Corps on February 9, 1870. Responsibility for the weather service moved to the Department of Agriculture in 1890 and then to the Department of Commerce in 1940.

The foundations of what was to become the National Weather Service were laid in Cincinnati in 1869. Cleveland Abbe, having pursued a varied career that led him to astronomy, was the newly-appointed head of the Cincinnati Observatory. The observatory was a smalltime affair that was mostly used to entertain the public. But Abbe was passionate about broad areas of science. He appreciated that astronomical viewing conditions were a function of the weather and saw the need for better weather forecasts, not just for astronomy but for people's daily lives. Seeing an unfilled need, Abbe switched his passion from the far heavens to those a little closer to home.

Abbe saw the potential of the telegraph system as a way to relay large quantities of data to a central office for analysis and forecasting. He proposed to the Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce and the Western Union telegraph company that they underwrite the costs of setting up observation stations around the region. Western Union agreed to provide low cost transmission of weather data to the observatory for his analysis. In return, Abbe offered to provide free forecasts three times a day for publication in the regional newspapers. An experimental trial ran for a number of months which proved the worth of the idea.

The U.S. Congress was urged to expand the concept nationally and hence the government formed the National Weather Service under the auspices of the Army Signal Corps. Abbe was the first director. He worked to advance meteorology as a recognized science within the Weather Service amd petitioned other universities to start programs in the field. While efforts within the Weather Service advanced (albeit at a maddeningly slow pace), universities did not create meteorology departments until the 1930's.

So once again, we see the familiar pattern of someone with passion who perseveres to create something of great importance. Abbe worked patiently and tirelessly to bring the National Weather Service into being as a respected scientific organization. Few things are ever created without the Cleveland Abbe's of the world. They do not have to be flamboyant or abrasive. They need only to believe that they are creating something much larger than themselves.

Abbe once wrote in a letter to his father, "I have started that which the country will not willingly let die." How right he was.

After a lifetime of service to the Weather Service, Cleveland Abbe died on October 28, 1916.

[Image from Wikipedia]

Sunday, December 2, 2007

CP-1

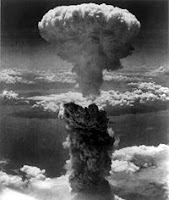

Sixty five years ago today (December 2, 1942), the world moved into a new and more dangerous era. CP-1 is the code designation for Chicago Pile-1, the first nuclear fission pile built in an abandoned squash court at the University if Chicago. Enrico Fermi and his colleagues who built the pile were part of the Manhattan Project. The goal was to develop an atomic bomb before the Germans did.

The experimental reactor was built under the abandoned west stands of Stagg Field stadium. The pile contained 771,000 pounds of graphite, 80,590 pounds of uranium ore, and 12,400 pounds of uranium metal. It was a crude affair about the size of a two-car garage. The pile was constructed quickly (but carefully) and was held together with a lumber frame to keep the massive weight of the sphere of bricks in place.

The physicists had been testing the pile all morning of December 2nd. Richard Rhodes in The Making of the Atomic Bomb describes the scene in the afternoon of that day:

At two in the afternoon they prepared to continue the experiment...Forty-two people now occupied the squash court, most of them crowded onto the balcony. Fermi ordered all but one of the cadmium control rods again unlocked and removed. He asked Weil to set the last rod at one of the earlier morning settings and compared pile intensity to the earlier reading. When measurements checked he directed Weil to remove the rod to the last setting before lunch, about seven feet out...'This time, he told Weil, 'take the control rod out twelve inches.' Weil withdrew the cadmium rod...'This is going to do it,' Fermi told Compton. The director of the plutonium project had found a place for himself at Fermi's side. 'Now it will become self-sustaining. The trace [on the recorder] will climb and continue to climb; it will not level off.'...Again and again the scale of the recorder had to be changed to accommodate the neutron intensity which was increasing more and more rapidly. Suddenly Fermi raised his hand. 'The pile has gone critical,' he announced. No one present had any doubt of it. Fermi allowed himself a grin. Its neutron intensity was then doubling every two minutes. Left uncontrolled for an hour and a half, that rate of increase would have carried it to a million kilowatts. Long before so extreme a runaway it would have killed anyone left in the room and melted down.

'Then everyone began to wonder why he didn't shut the pile off,' Anderson [a physicist present] continues. "But Fermi was completely calm. he waited another minute, then another, and then when it seemed that the anxiety was too much to bear, he ordered, 'ZIP in!' It was 3:53 PM. Fermi had run the pile for 4.5 minutes at one-half watt and brought to fruition all the years of discovery and experiment. Men had controlled the release of energy from the atomic nucleus.

Rhodes states that the decision to build the pile and run what could have turned into a runaway nuclear experiment akin to Chernobyl was left entirely to the project management. Even the president of the University was not informed. Fermi was not worried about an accident but this was the first critical fission reaction in history. Chicago might never have been the same.

Another Manhattan Project physicist, Leo Szilard, stayed behind with Fermi when everyone else had left after the celebrations and toasts. Rhodes quotes Szilard as saying:

There was a crowd there and then Fermi and I stayed there alone. I shook hands with Fermi and I said I thought this day would go down as a black day in the history of mankind.

Of course, subsequent events proved Szilard right. The nuclear genie had been released and it has never been put back in the bottle. We now live within the constant shadow of nuclear warheads. We go on our way, hardly thinking about the destructive power that can be unleashed. Clearly, nuclear fission also has a positive side: nuclear energy. But when do the cons outweigh the pros? If it is possible to develop a technology, must it be developed? Will it be developed, regardless? Do we really have the ability to control the technology we develop or are we inexorably driven by the newest discoveries in science? These are troubling questions. They ought to be troubling questions. Ultimately, are we in control of our own destiny?

It is a profound and necessary truth that the deep things in science are not found because they are useful; they are found because it was possible to find them.

- J. Robert Oppenheimer

[Image of atomic bomb exploding over Nagasaki, Japan, August 9, 1945]

Saturday, December 1, 2007

Chatter in the Night Sky

I was flying home last night. The skies were clear down the entire East Coast. The cabin entertainment system let me tune in to the air traffic control channel for our flight. For over an hour, I sat and listened to the chatter on the airwaves as I watched the lights of the cities drift by. Instead of a silent sky, I heard the night filled with the voices of air traffic controllers and pilots talking to each other about altitudes, routes, flight track crossings points, weather and flight conditions.

"Atlanta, United 1521. You may climb to three eight zero and maintain vector one eight zero."

"United 1521, roger Atlanta, climbing to three eight zero."

"United 1521, hand off to Jacksonville ATC. Frequency one three three point two seven."

"Roger, Atlanta. One three three point two seven. Goodnight."

There was a clear sense of competence and professionalism even in these brief cryptic remarks. At one point, I heard a pilot comment that he had been flying up from New Orleans and had to make the trip at the (relatively low) altitude of 27,000 feet to avoid turbulence. The air traffic controller responded dryly, "You took the scenic route."

Air traffic control as a technology grew up with the airplane and especially, the airline industry. Like most new systems, it started out privately, built by those who wanted it most, the airports and the airlines. By World War II, it had moved under the control of Federal Government's Civil Aeronautics Administration. But it was the advent of commercial radar in 1960 that revolutionized air traffic control. Advances in technology over that last 50 years have allowed relatively safe flights in an evermore crowded sky.

But behind all this technology are the people I listened to last night: the pilots and air traffic controllers who make a relaxed, safe flight possible. I trust these people to get me to my destination in one piece. But it is always this way with complex technology systems. In everything from hospital operating rooms to nuclear power plant control rooms, we demand trained professionals to run our technologies for us. And day in and day out, they do just that. In our complex world, we cannot live any other way. But the voices and the chatter that I heard last night tells me that these are still people. People I can trust.

We landed without incident right on schedule. When I went outside to get my car, the sky seemed strangely quiet.

By the way, if you want to listen in live to the ATC chatter, you can do it here.

[Image of Washington, DC Air Traffic Control from Wikipedia]

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)